The right to throw out this bill

Proponents of legalising assisted suicide (like Baroness Harman) have argued strenuously that the House of Lords must not stand in the way of a bill passed by the elected chamber — the House of Commons. Many have cited a principle called the “Salisbury doctrine”, which:

“As generally understood today, means that the House of Lords should not reject at second or third reading Government Bills brought from the House of Commons for which the Government has a mandate from the nation… Since 1945, the Salisbury doctrine has been taken to apply to Bills passed by the Commons which the party forming the Government has foreshadowed in its General Election manifesto.”

At the 2024 General Election, Labour did not even mention “assisted dying” in its manifesto; nor for that matter did the Scottish National Party, Plaid Cymru, Reform UK or the Social Democratic Party. The Conservatives stressed that it was “a matter of conscience”, and the Liberal Democrats went no further than to pledge Parliamentary time and a free vote. Only the Greens, who secured 6.7% of votes, promised to “support a change in the law”.

The Leadbeater Bill is a Private Member’s Bill, not a Government Bill, and the Government has repeatedly stressed its neutrality. The Salisbury Convention does not apply. As constitutional authority Walter Bagehot put it, the Lords “can reject Bills on which the House of Commons is not yet thoroughly in earnest – upon which the nation is not yet determined.” This is crucial, given that:

- The Bill passed the Commons at Third Reading with a reduced majority of 23, and with less than half of MPs voting in favour: the House of Commons is not yet thoroughly in earnest.

- We already knew that much-trumpeted public support for a change in the law collapses (to 11%) when the arguments and evidence against are heard, and polling published in September found that 70% of those who expressed an opinion believe “peers have every right to vote against non-government legislation if they consider that it poses a significant risk to vulnerable lives”: the nation is not yet determined.

Supporters of the Bill have contradicted themselves in the rush to curtail Lords scrutiny: journalists Andrew Rawnsley and Simon Jenkins have said it would be “disgraceful” and “a democratic outrage” for Peers to reject the Bill, despite both having written previously about the Lords’ right to contradict the Commons. Jenkins once exclaimed (on a different policy):

“What should the Lords now do? The answer screams over the rooftops. They should vote the wretched bill down and send it back to the Commons.”

Peers are contradicting themselves too. On the eve of Second Reading in the House of Lords, 65 sent a letter to the press (and also eventually to its supposed recipients – other Peers) arguing that “it is not our role to frustrate the clear democratic mandate expressed by elected members.” Yet it then turned out that, to give just one example, “21 of them were perfectly happy to vote to block the 2014 European Union (Referendum) Bill, a Private Member’s Bill which had passed the Commons.”

Lord Falconer, the Bill’s sponsor in the Lords, has himself voted against bills passed by MPs — including one with a majority three times that of the Leadbeater Bill:

2/- On 12th October 2011 Lord Falconer himself was one of 220 Peers, mostly Labour, who voted against the Coalition Govt’s Health & Social Care Bill at its Lords 2nd Reading, despite it having passed the Commons with a majority of 86 at 2nd Reading and 65 at 3rd Reading.

— Richard Chapman (@SelsdonChapman) June 24, 2025

He wrote in the Guardian several years ago that:

“The House of Lords has been an effective means of ensuring that the Commons genuinely thinks again about proposals that go too far or undermine the values of our constitution… Whatever proposals for longer-term reform emerge the Lords in its current form will be with us for some time. Its independence from the executive is its strongest characteristic.”

Journalist Dan Hitchens poses the question:

“Has anyone campaigned longer, harder and more eloquently than Lord Falconer for the right of the upper house to reject proposals approved by the Commons?”

We agree with Lord Falconer’s 2018 comment:

“How very unattractive for a politician to defend the principle of the House of Lords as long he agrees with the amendments its makes but then threatens the Lords with being burnt down if he disagrees with their amendments. Very unBritish.”

The Lords Constitution Committee (whose members include a former Lord Chief Justice and two KCs) concluded in September that:

‘Given that this Bill is a private members’ bill and that it deals with a morally significant subject, close and detailed scrutiny by both Houses is particularly important.

‘The House of Lords plays an important role in the legislative process. It is constitutionally appropriate for the House to scrutinise the Bill and, if so minded, vote to amend, or reject it.’

Leaving all of this aside, it would be quite wrong to talk of the House of Lords ‘blocking’ the Bill. Peers are fully aware of their “subordinate” role, and the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949 mean that even if the House of Lords rejects a Bill, if MPs are still convinced that that text should become law, they can override or sidestep the Lords a year later.

But would MPs still want to pass this bill?

Scrutinise and strengthen

Campaigners for a change in the law have decried the number of amendments lodged in the Lords – now more than 1,000 – but have said less about the substance of proposals. On the first day of Committee, Peers considered the particular needs of Wales and people’s ability to make free decisions; in the second session, they considered amendments to guard against coercion, undue influence, domestic abuse, financial abuse, internalised pressures…

As Sir David Beamish, former Clerk of the Parliaments, told the Hansard Society:

“We haven’t seen anything look like filibustering… I don’t think [tabling “a vast number of amendments” is] illegitimate. They’ve been discussing important points of principles… You can understand that Members who are anxious about, in particular, people being pressured into an early death, want to make jolly sure that the Bill is fit for the statute book before it gets there.”

These anxieties are shared by a great many experts.

Seems the government really believes the bill can be made safe.

Here are some other verdicts: https://t.co/QJdEOHMTgJ pic.twitter.com/T3Rrps6hLy

— Dan Hitchens (@ddhitchens) November 26, 2025

So even if people oppose particular amendments, they cannot reasonably write off scrutiny as a tactic. No wonder there were such indignant responses to Baroness Hayter of Kentish Town, when she said in the House on 21 November:

“We have to ask… whether these discussions about definition are really about that, or whether they are about trying to stop the Bill… whether those who want the wording changed would then support the Bill. If they would, let us get down to discussing that, but if they are never going to, they are wasting the time of those who want it to go through.”

Psychiatrist Baroness Hollins interjected:

“Every amendment that I have tabled is designed to make the Bill better and I feel quite concerned to be accused of time-wasting.”

KC Lord Carlile of Berriew said:

“The reason we wish to have… [these] discussions… was so that, believe it or not, we can make a judgment as to whether we are prepared to support the Bill, or to be silent on whether we support the Bill, or to oppose it at Third Reading. It is unworthy of the noble Baroness to allege that all of us here who are expressing concerns are wasting time.”

Former High Court judge Baroness Butler-Sloss added:

“There are many of us who do not like the Bill, but there is a real possibility, [even] probability, that the Bill will pass, and if it passes, we want it better than it is at the moment. Consequently, we are not wasting time.”

More time

Just four days were assigned for the Committee of the Whole House, and various Peers said this was inadequate. By way of comparison:

- 12 days were needed to consider 725 amendments to the Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill

- 8 days were needed for 652 amendments to the Planning and Infrastructure Bill

- 11 days were needed for 646 amendments to the Employment Rights Bill

On Wednesday 26 November, Government Chief Whip Lord Kennedy of Southwark announced that he had “arranged for the House to sit on eight additional Fridays in the new year”, and so in addition to the sittings on 5 and 12 December, “those Fridays when the [Leadbeater] Bill will be considered will be: 9 January; 16 January, alongside some other PMB business; 23 January; 30 January; 6 February; 27 February, 13 March; 20 March; 27 March; and 24 April.”

The House of Lords is unelected, but there are checks in place to guarantee the primacy of the Commons. Within that framework, the upper house — whose members include eminent doctors, disability rights advocates, lawyers, and former judges — has both a right and a responsibility to scrutinise and seek to improve any bill, and even to reject a bill “for which the Government has… [no] mandate from the nation” if “they consider that it poses a significant risk to vulnerable lives.”

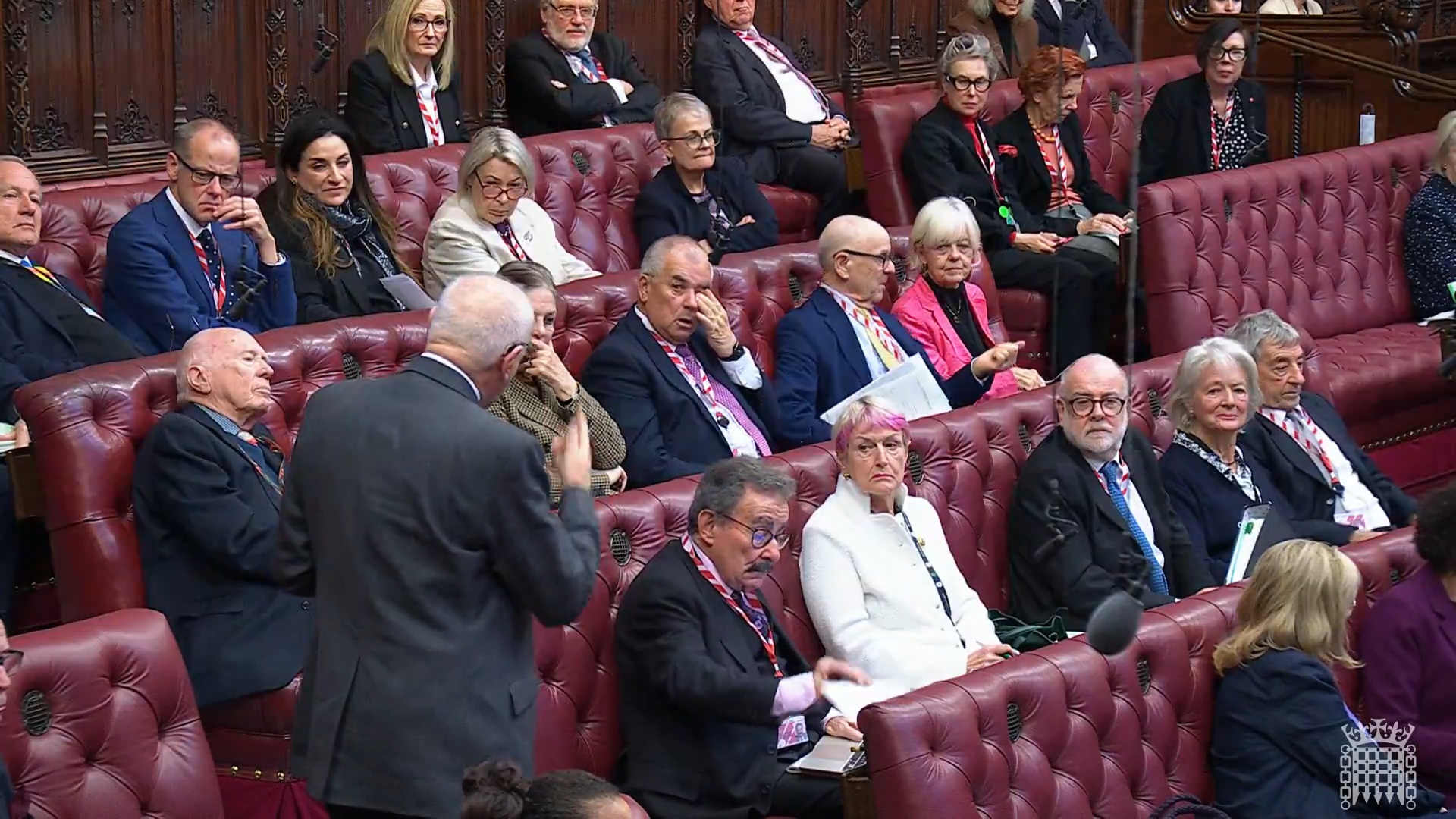

A House of Lords appreciation thread.

Here are 20 peers doing a fine job scrutinising the Leadbeater/Falconer bill: pic.twitter.com/eoqN83qEfb

— Dan Hitchens (@ddhitchens) November 23, 2025